|

An Interview

In which David Bailin interviews me for for his AETN

blog.

What is your basic approach to art and how has it changed?

Do I have an approach? I kind of wish I did, it would make things

easier. Even though art is supposed to bring order to chaos,

the creative process itself is very chaotic. Images come out

of nowhere - no, not out of nowhere, out of the visible or audible

world or out of some unknown or forgotten or forbidden part of

myself, or from some combination of all those - and they come,

or don't come, on their own timetable, not mine. But when they

come they demand to be made into some object. It's more of an

addiction than an approach. How does an addict approach his addiction?

An "approach" would have to

be based on ideas-like, "Let's see, what can I paint that

somebody might actually buy before I have to move under a bridge?"

But that would be a rational approach. I jokingly called a recent

exhibition of mine "Still Crazy," but there does seem

to be something seriously irrational about art. Why would a sane

person take it up? Jose Ortega says ideas are scarecrows to frighten

away reality. This is why art can be dangerous-because it can

penetrate our defenses against the truth and strip us bare. In

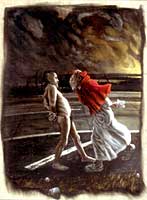

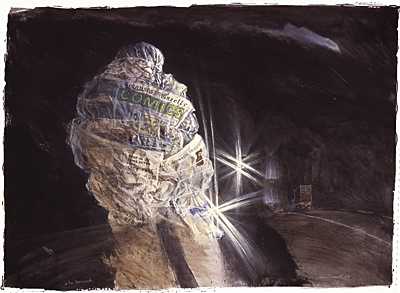

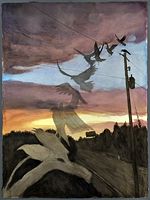

retrospect, I can see that my painting Flash Flood from

2002 is an illustration of this--hilarious and terrifying at

the same time! The hero myth exposed! But there's no 12-step

program that I know of.

But didn't you used to be a writer?

Yes, I was clean for about eight years

while I was trying to write the Great Apocalyptic Novel - well,

not really, because writing is just another kind of obsession,

but at least I was away from visual art. I was also on the road

with my wife and kids in a bus called Toad Hall, Mr. Toad on

a mission to save the planet, gaily bedight, a gallant knight,

in search of El Dorado (not the one in Arkansas). I wanted to

set up a self-sustaining, off-the-grid, solar-and pig-shit-powered

homestead and write about it, thus preventing the coming industrial-ecological

collapse.

| |

But he grew old --

This knight so bold --

And -- o'er his heart a shadow

Fell as he found

No spot of ground

That looked like El Dorado.

(From "El Dorado" byEdgar

Allen Poe)

Linocut from 1991

|

Eldorado, 1999,

linocut |

Near the end of this crusade I happened to see

the watercolors of Hubert Shuptrine in a book of James Dickey's

poems. They intrigued me because of their range of values--much

deeper darks than I was used to seeing in watercolors, and in

all innocence I began to steal time from the typewriter to fool

around with watercolors. I built an "easel" that fit

onto the steering wheel of the bus. That was my first "studio"

since leaving Florida in 1972. My paintings weren't serious,

there were no ideas behind them, I was just playing. I didn't

recognize the siren's song and there was nobody to tie me to

the mast. Pretty soon I began selling my watercolors and I was

hooked again.

This was in Little Rock?

No, but this is where we ended up after

five years on the road.

My publisher had gone out of business, the

bus broke down and we had to get jobs. I discovered the photo-realists

in a show at the Arkansas Arts Center and I sort of became one

of them - but in watercolor. After a few years of this - during

which I built up a pretty good group of collectors - I realized

I had become a prisoner of both the medium and the photograph.

I had painted in oils in Florida but didn't really know what

I was doing technically, and now all I knew how to do was watercolor.

And the photograph had become a dictator.

So I dumped the camera cold turkey and started carrying a sketchpad

with me everywhere. I had to learn to see for the first time

and learn to draw all over again. I discovered that the camera

didn't see things the way my eyes did. Also, my work turned dark,

both tonally and thematically, too dark for watercolor and Arkansas.

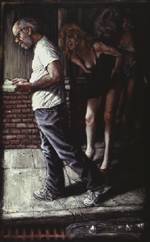

I got good at drawing in the dark, inside strip clubs and on

the shoulders of highways at night.

I lost all my collectors and my gallery strongly

advised me to lighten up, but it was no use. I can't seem to

do art unless I'm discovering something new. You asked me before

why I work in so many different media, and I said it's because

I'm easily bored, but what that means is that I have to keep

making new discoveries or I run out of steam. I can't "search"

for discoveries because I don't know what I'm looking for, but

by working in 2, 3, and 4 dimensions, maybe I'm expanding the

field of possibilities. It's like what Faust said to the Devil:

"When I've seen it all and done it all, to hell with it."

So one of the things I discovered at that time

was the futility of trying to be unique. Modernism was over,

we had stripped art of everything we could think of, even the

art object itself, trying to get down to the essence, leaving

only the "concept" behind like a ghost. There was nothing

more to get rid of, Number One was a monkey, and painting was

dead. Somehow that seemed liberating to me. I had always loved

the paintings of Caravaggio and Rembrandt and now I felt free

to try that myself. I got all the books I could find on Old Master

painting techniques, learned how to make paint from dry pigments,

the panels and canvases they used, the whole nine yards. The

upshot was that only after I started imitating Rembrandt did

people start saying my paintings were unique!

A lot of your themes at that time came from mythology. What books

inspired you?

Well, "themes" sounds like something premeditated.

I was never that organized. But I was reading Joseph Campbell

and Robert Graves, and I realized that myth and religion were

not only attempts to deny death, as Ernest Becker says, but were

also timeless reflections of our psyches. All our hungers and

fears, joys and miseries, all our psychoses and obsessions were

dramatized in myths long before Freud and Jung discovered them

in our heads. So all my mythological images are set in my own

time, and I'm usually the protagonist. Okay, always the protagonist.

I used to think I used myself as a model because I couldn't afford

a real model , and it wasn't really me in the paintings, but

eventually I realized it was me after all. I was Acteon and the

Crab King and all the others. This is what can happen when you

go with the images first and deal with the ideas later. You reveal

yourself without knowing it. But if I ask the Muse, "What

do you mean by that?" nothing will get painted.

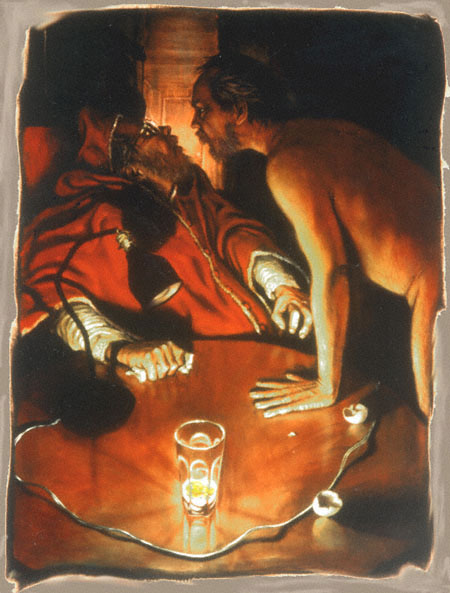

Another book that ended up generating a long series of paintings

that I didn't know was a series was Dostoyevsky's The Brothers

Karamazov, specifically the chapter called "The Grand

Inquisitor," Ivan's story about a second coming of Christ

during the Spanish Inquisition. It was about this time that I

was becoming fascinated by the concept of the double, the döppelganger,

and I had also been looking at El Greco's portrait of Cardinal

Niño de Guevara, and the image I got was a kind of twisted

conflation of all that. I painted myself as both the Cardinal

and the prisoner and called it "The Question," a title

I think I got from Sartre's Being and Nothingness, which

I was also reading at the time. Sartre said the question breaks

open the egg of the closed universe.

That was in 1991, and for years after that

everything I painted had these guys in it! For me they symbolized

the existential paradox - that we are animals with self-consciousness,

and the animal and the self can neither be reconciled nor separated.

For "animal" read "image," and for "self"

read "idea." You can't have one without the other,

and "The Question" can never be answered.

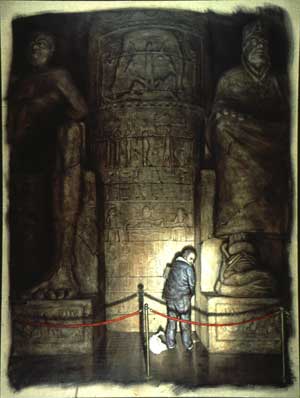

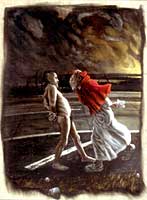

The Storm, 1992,

oil on linen,

48 x 36 inches |

Study for "Hiway 61",

1993, conte & acrylic on

paper, 34 x 26 inches |

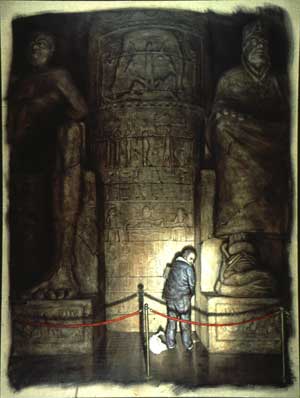

The Trespasser,

1993, oil/wax on linen,

60 x 48 in. |

The Kiss, 1992,

oil on linen, 48 x 36 inches |

The Temptation, 1991, The Temptation, 1991,

charcoal & spray enamel

on paper, 28 x 38 in. |

But I was so locked up in all this - as in

A Man Reading - that life was passing me by, and I finally

managed to break out of it. The last one was All the King's

Horses. They were gone, egg and all.

Since then you've gotten into sculpture,

printmaking and animation. What were the biggest changes to your

work over the years?

1189i.jpg)

Roadkill, bronze,

2010, 9 x 8 x 13 inches |

to New York

in 2005 where I saw an animated film by William Kentridge.

That started me on a whole other addiction! Now I could bring

my images to life - after the year or so It took me to learn

how to do it. It was a fateful investigation into time itself,

into the moments that we never see because they go by too fast.

I had to do 24 drawings to get 1 second of video, so I had to

slow down my creative metabolism to a crawl. It brings us back

to the insanity of art, but I was hooked. I had become Dr. Frankenstein.

"It's aliiiiiiiive!" |

But aside from the technical problems, working

in the fourth dimension had a profound influence on my other

work. These "images" I've been talking about were always

that perfect moment that you could immortalize on paper or canvas

or in bronze or whatever. But now that perfect moment had a past

and a future, a beginning and an end. I had brought my images

to life, but I also brought them to death. I was right back at

that existential dilemma: no life without death. Now when I did

a painting it looked like a multiple exposure photo.

I found I could do this even with sculpture-show

movement and transparency in a solid opaque material. Thinking

about it now, that seems like another metaphor for existence

vs. essence, image vs. idea, animal vs. self.

But maybe my work hasn't changed as much thematically

as it has technically. For instance, the double has haunted my

work ever since "The Question." My last animation is

an example. Aristeas is supposed to have left his body in the

form of a raven and hung out with Apollo for years in a state

of ecstasy. This is the double! One part of us wants freedom,

the other part wants security. One part loves chaos, the other

needs order. The animal is immortal, the self knows it will die.

In the Inuit religion Raven is both the creator of the universe

and a trickster, a dirty old man. The crow, you know, has been

in my images for a long time. The raven and the crow, for all

their intelligence and beauty, live on dead animals, so they

are natural symbols for man with his double nature.

Art seems to exist at the interface of this duality,

drawing its energy from both sides. If it expresses just one

side or the other-the beauty without the ugliness, the humor

without the pain - it seems empty or trivial. To me, anyway.

Sometimes the images that ambush me do indeed seem trivial: a

roll of toilet paper, a coffee cup, the night sky. But maybe

something in my unconscious - my muse! - recognizes that duality,

the idea in the image, even though I don't figure it out until

later. But I think the artist lives for those stunning moments,

and then seeing them reborn from his own hands, and always in

fear that they will abandon him. That's the addiction.

So what's going on in your head now?

You don't want to know.

No, seriously. What's happening in the studio? What are you

reading?

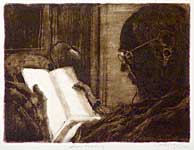

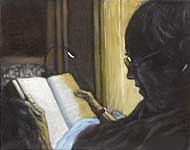

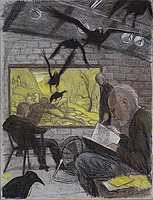

Janet took a picture of me with her phone last week while I was

reading in bed. Actually, I was asleep. I always denied that

I dropped off while reading, so this was her proof. It was a

joke shot, the old fart snoring over his book, but something

about the composition or the lighting grabbed me. It turned out

to be one of those unexpected moments, so I went with it. Hey,

the muse had not been singing, I had nothing else going, give

me a break. The next day I did a monotype from the photo, and

now I'm working on a painting and a linocut. It's called "Sleep

Reading," a variation of speed reading.

Sleep Reading,

2012, monotype,

image 8 x 10 ½ inches |

Sleep Reading,

2012, oil on canvas, 16 x 20 inches,

in progress |

Sleep Reading,

2-color linocut,

image 5 x 7 inches, edition of 12 |

The book I was sleep reading is called From

Eternity to Here by Sean Carroll, and it's about time - actually,

about how time is a function of entropy and the Second Law of

Thermodynamics. I'm also reading a book called The Botany

of Desire, which basically asks the question, "Did we

domesticate the apple, or did the apple domesticate us?"

And before that I read E.O. Wilson's The Social Conquest of

Earth, which shows that, existentially speaking, there's

not that much difference between humans and ants, except that

ants are altruistic robots and humans are more destructive. I

should also mention that a few months ago I read the 30-year

update of the book which started me off on my crusade to save

the world, Limits to Growth, and found that nothing had

changed in the data since then to slow down the exponential growth

of population, pollution and fossil fuel use and that we were

even deeper into overshoot mode than back then. The ecological-industrial

collapse was still on schedule for around 2050. But the books

I mentioned, as well as my Aristeas animation, are giving me

a somewhat different view of this than I had in my activist phase

back in '72.

Working on the waves in the background of Aristeas, drawing frame

after frame, plenty of time to think, I began to see everything

as a wave. Careers, individuals, civilizations, species, ecosystems,

all roll along in an orderly way, lowering their own entropy

(that is, their chaos) by raising that of their neighbors, until

they encounter some obstacle, like a beach or the food runs out,

or the oil, and then they may rise up in a magnificent moment

of fame and glory, go into overshoot mode, crash to the sand

and get sucked back into the sea they came from. It's just a

natural cycle. It's not us against nature. We are nature! All

of this - cars, computers, wars - it's all nature! We think we're

special because we have self-consciousness and can imagine infinity

and draw pictures and write poems, but the apple gets along just

fine, using us to spread its genes around, without imagination,

consciousness or even mobility. From the point of view of ET

a couple light years away, it wouldn't make any difference whether

we destroy the biosphere or a colliding asteroid does it, the

biosphere is toast either way. Both are just natural phenomena!

I grew up on the beach in south Florida, watching, hearing and

swimming in these waves, but I didn't really see them until now,

trying to draw their secret moments, using a surf video, seventy

years later, landlocked in Arkansas.

But the strange thing about art is that some

of its most depressing and frightening discoveries can reveal

moments of awe-inspiring beauty! There's the dichotomy of human

nature again: its self-destructive cruelty on the one hand and

its search for beauty on the other. You just finished Moby Dick

- finally! - and now you know that Captain Ahab lurks in the

hearts of all artists to some degree. We are all obsessed with

some whale or other. But remember the ending? "…and

the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago."

|

The Temptation, 1991,

The Temptation, 1991,

instal1333t.jpg)

1189i.jpg)

scpt-i.jpg)