|

[The Narcissistic Sinner: Warren Criswell's Pictures, by Donald Kuspit, page 2]

It is a wonderful fantasy—a magnificent wish fulfillment, an ironical balancing of pleasure and reality principles—made all the more magnificent by the dense, hand-ground paint Criswell uses. It will last forever, or at least as long as the stone of the Egyptian temple. But for all the clarity of the image and its meticulous execution, Criswell implies that it is a fleeting illusion. |

|

||||

| Its brushy, unstable edges—it does not completely fill the canvas—suggest that it is a dream. (Virtually all of Criswell's works show a similar picture-within-a-picture concept, or rather, a vision-in-a-void concept.) Its tenebrism also confirms its hallucinatory character, as does the startling detail of the red rope and its shadow, lying low and cutting horizontally across the very vertical picture. | |||||

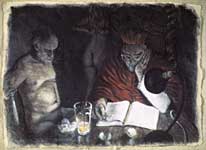

| Criswell will awaken from this particular dream of himself, and record it, but he will quickly have another with similar content and structure, and record it with the same painstaking attention to hallucinatory detail. He invariably shows himself doubled, sometimes tripled, as in Highway 61, 1993. It is the self against the self, in conflict with itself: carnal Criswell threatened by the Grand-Inquisitor-Cardinal-Superego. Thus, in The Storm, 1993, a Cardinal Criswell—he wears the red vestments of the Inquisition—confronts a naked Criswell. His hands are tied behind him, while the Cardinal's hands, behind him, hold a no doubt incriminating document. |

|

||||

|

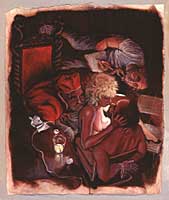

Their nightmarish encounter—and virtually all of Criswell's pictures are aggressive, if also erotic nightmares—occurs on the side of a highway, that peculiar no-man's-land that is America's contribution to civilization. The eggshells that litter that desert reappear on the table of The Question, 1991. In that dream picture the same naked, bound Criswell faces the same Cardinal Criswell, who interrogates him with the aid of an electric lamp. In The Kiss, 1992, a liberated Criswell tries to kiss the startled Cardinal Criswell at the same table. This may be a reference to Ivan's parable of "The Grand Inquisitor" in Dostoevsky's novel The Brothers Karamazov, in which Christ returns to earth during the Spanish Inquisition. Indeed, the double egg yolk in the glass is illuminated like the infant Christ in a medieval nativity, and this life symbol also appears in the drawing The Cardinal Reading, 1993. In Dostoevsky's story the captured Christ stands up after his long interrogation and kisses the Cardinal-Inquisitor, who had planned to burn him in the morning at the auto-da-fe. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

But if Criswell's version of this scene is to be read as an attempt to reunify his fragmented self, it is obvious—to judge from the expression of horror on the Cardinal's face—that is does not succeed. Nor does the Christ reference negate his prisoner-self's carnal nature: in The Cardinal Reading the naked Criswell, once again bound, sleeps, while in the shadowy background a woman is getting dressed. In Table Dancer and Two Manikins, both of 1992, Criswell gives his game away, as it were: both figures are puppets in a play, more particularly, projections of his psyche. The naked figure is sexually obsessed but inhibited by the Cardinal, who has bound him—but at the same time tempts him in Table Dancer (perhaps a reference to the Devil's temptation of Christ, as told by Dostoevsky's Grand Inquisitor). The same conflicted attitude to woman—simultaneously guilty and lustful—is suggested by Changing Woman, 1992. Both figures, in miniature, are laid out on the table in front of a naked woman. She holds the glass of egg yolks as though it was the vessel of a sacrament—a symbol of her sacred, mysterious womb. (Changing Woman, in the Navajo religion, is the virgin mother of twin heroes who went on a quest to seek their origins.) The Animation, 1992, makes it clear that they are fighting over—performing for, being animated by—the woman. Is she the Great Mother or the Great Whore, or both? |

|

||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

They cannot put the Humpty Dumpty Criswell feels he is together again after his "fall," a term which of course connotes sexual—"original"—sin, and the mythic origin of mortality. This is why Criswell expects to be punished, to crack up—to be hit by a car, captured by a guard and imprisoned, that is condemned by the spectator—by the Other (no doubt for showing himself literally as well as emotionally naked, and thus violating a social taboo, especially against the latter). In the same way, The Diver, Two Men on Stilts, and The Pool contain vast voids. Emptiness is vulgar rather than solemn in America, that is, a sign of indifference rather than interiority. Criswell's brilliant rendering of all-American emptiness symbolizes his feeling of anxious emptiness in an indifferent world. It is in effect the punishment the Cardinal threatens him with: to escape the void he must endure the exhaustion of his conflict, more particularly, of his restraint of his lust. His empty space is always ominous and threatening, as in Two Men on Stilts, where the sky is full of smoke and fire, and in The Diver, where the sea is a stormy abyss. Both suggest infernal suffering, punishment, and doom. |

|

||||

All images and text on this Web site Copyright © 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000 by Warren Criswell |

|||||

t.jpg)