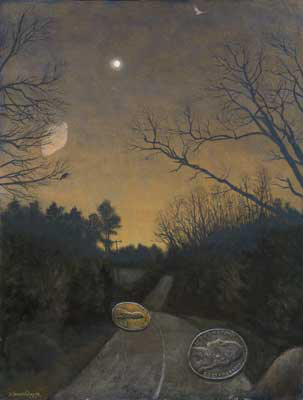

When we get older the world has gotten older too. Fewer things surprise us. We start repeating ourselves without realizing it. Routine takes over our lives. Time seems to speed up and we can see Death down the road. If you're a creative person, you need to reboot. I must have seen animation as a way to do that, but it came at a price. Like Poussin’s shepherds I had to give up on immortality. In bringing my drawings to life, I also brought them to death. As Hector Berlioz said, "Time is a great teacher, but unfortunately it kills all its pupils." Giotto’s perfect moment now had a past and future, a beginning and an end. A painting seems to exist eternally, but I don’t have that feeling with an animation. I feel almost like a performance artist who can never repeat his performance. It seems to blur the distinction between art and life, a kind of branding by the stigmata of time. Of course a movie can be played over and over,

just as a musical composition can, but there’s something

about its existence in time, the addition of a fourth dimension,

that gives me a feeling of transience, of passing.

Music exists in time, painting and sculpture in space. Animation can be a kind of bridge between the two. As a painter, when I thought about making my images move, they always moved to music. But, metaphorically speaking, it's a shaky bridge. The artist, like everyone else, is in the river of time, but we think an exception has been made in our case, because we’re able to make stuff and throw it up on the riverbank (as long as we can believe in the riverbank). Since Giotto, we capture a moment and immortalize it. As an animator you give this up. You're caught in the flow. The bridge falls into the river. |

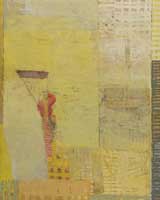

Aristeas I, 1996, oil on wood, 24 x 17 inches |

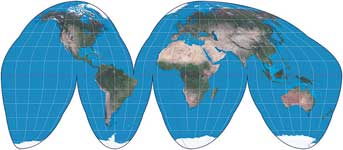

Aristeas, according to a story by Herodotus, found a way avoid falling in. He flew away! I painted this in 1996 and recently decided to animate it. Aristeas is supposed to have left his mortal body in the form of a raven and hung out with Apollo on his travels around the world. He wrote a poem of his adventures and part of it is preserved by Longinus in his essay "On the Sublime," written in the 1st Century AD. "This too we remark in great wonder: men dwell in the water, far from land in the midst of the sea. Unlucky wights they are, for they suffer grievously, with their eyes on the stars but their life amidst the waves. Assuredly, lifting their hands to the gods, many are the prayers which they must make, with entrails sorely tossed." |

| Seasick, I think he means. But as I worked on the background of this animation—I was working from a video of surf—I began to feel like those mermen, living inside the wave, but in extreme slow-motion, drawing frame after frame, sometimes 24 in a day, which would give me 1 to 2 seconds of movement. | |

|

I keep having to use this quote from Conan Doyle, because it's so relevant to my experience in art. Sherlock says, "Quite so, Watson. You see but you do not observe. The distinction is clear." Living inside these waves, I began to think of everything as waves—the lives of individuals, of civilizations, of species, all rolling through the ecosystem, lowering entropy for a while but, like the wave as it approaches shallow water and goes into overshoot mode, having to pay it back eventually. But it's a glorious moment, this breaking of the wave. Maybe it's like McCarthy said, "beauty and loss are one." So I was having philosophical thoughts like

these but at the same time I was discovering the intimate secrets

of the waves. I heard an interview with Frank Langella, the actor

who played Nixon in "Nixon and Frost." He said he couldn't

get Nixon right until he accidentally hit the slow-motion button.

Watching him like that, he said, revealed to him the soul of

Richard Nixon. He said he could see everything Nixon was hiding. After I finished this animation I read a review of Karl Knausgaard's novel "My Struggle: Book One" (2009), and I can't resist including his closing lines here, because they mirror my thoughts while drawing the wave: "For humans are merely one form among many, which the world produces over and over again, not only in everything that lives but also in everything that does not live, drawn in sand, stone, and water. And death … was no more than a pipe that springs a leak, a branch that cracks in the wind, a jacket that slips off a clothes hanger and falls to the floor." And, he might have added, a wave that breaks on the beach. Here's my animation of Aristeas. |

|

After having that revelation I read Lee Smolin’s book Time Reborn: From the Crisis in Physics to the Future of the Universe. Parts of it echo– from a physicist’s point of view—what I was saying about the efforts of religion, art and science to stop time. And near the end he writes, “We’re accustomed to seeing ourselves as apart from nature and our technologies as impositions on the natural world. But whether we fantasize about our conquering nature or nature surviving us, we have reached the limits of the usefulness of the idea that we’re separate from nature. If we want to survive as a species, we need a new way of seeing ourselves, in which we and everything we make and do are as natural as the cycles of carbon and oxygen we emerged from and in which we participate with every breath.” H. G. Wells has a great line near the end of his novel Tono-Bungay, where a trip down the Thames becomes a metaphor for the transience of life and art. "The river passes--London passes, England passes. We are all things that make and pass, striving upon a hidden mission, out to the open sea.“

|

|||||

|

Cars, 2011, Charcoal on Paper, 84 x 96 inches

Connection: narrow; opinion, oil & mixed media on canvas

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Crow Descending, 2007, watercolor, 30 x 22½ inches |

Dead Crow Walking, 2007, acrylic & graphite on paper, 30 x 22½ inches |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

—and even my sculptures. But now I see that I was still attempting to stop time. The only difference was that instead of freezing just one moment, I was freezing several. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Low Flying Crow, 2009, cast aluminum, 7 x 22 x 2 inches |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I was amazed to discover that I could create the illusion of transparency—ghostly movement—in a solid material like clay or metal. But it's just another example of how our senses create the world we think of as reality. So my perfect moments now had a past and a future, a beginning and an end, just as each of us do. So what happened to my theory that art grew out of the knowledge of our own mortality? For that reason, sometimes I think my animations are closer to life than to art. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

But I’ll give T.S. Eliot the last word.

This is from his Four Quartets, and may express this puzzle as

well as any words can:

So with a heavy load of debt to my musical collaborators, especially the composers and performers Bob Boury and Steve Whiteaker, here are my Moments. Thank you very much, ladies and gentlemen. Warren Criswell, 2012 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Previous page ... Page 1... Page 2.. Page 3 All images and text on this Web site Copyright © 2004-2014 by Warren Criswell |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

t.jpg)