WARREN

CRISWELL, ANXIOUS REALIST

By Peter Frank |

The Question, 1993, oil on copper, 5 x 7 inches. Collection

of Rickey Medlock

Warren

Criswell's painting - and his drawing and printmaking no less

- troubles the waters of contemporary artistic discourse. Criswell's

work proposes that an entirely backward-looking stylistic approach

can act as a vehicle for entirely timely thoughts and sensations.

Furthermore, although supported by the post-modernist argument,

which encourages us not to dismiss an art such as Criswell's

out of hand, his work does not rely on the conceptual dodges

and self-conscious anachronisms we associate with post-modern

practice. While Criswell's subject matter brims with the passions

and disturbances of early 21st century life, it does not place

itself at a dissonant, ironic angle to his entirely realist manner

or technique. Rather, that manner, so thoroughly rooted in the

late 19th century, and that technique, based on examples from

the 16th (late Titian) and 17th (Rembrandt in particular), proves

its durability and suppleness in Criswell's hands, serving as

a graceful and powerful vehicle for the artist's sweeping narrative

focus.

|

Man in a Yellow Shirt,

2002, oil on linen, 24 x 18 inches |

Over

the past two hundred years the narrative impulse has risen and

fallen repeatedly throughout artistic practice. Considering that

those two centuries have been dominated by powerfully persuasive

communication technologies such as photography, cinema and television,

it is no surprise that the discourses in more traditional media

- themselves transformed by the liberating possibilities of abstraction

- have wrestled with the narrative "question". The

narrative is about the most provocative tradition in western

art; as such, its profoundly uneasy condition in contemporary

artistic practice - its relation to the novel, to theater, to

film, and also to less exalted, even kitschy aspects of visual

culture such as illustration and comic strips - only amplifies

its ability to engage us on a variety of levels. |

Many contemporary narrative painters

working in the United States exploit this newfound multivalence,

not only mastering the formal and physical obduracies of traditional

artistic media in order to meet the demands of pictorial storytelling,

but developing a narrative practice whose peculiarities root

it in those media. They have developed a not-quite-surrealism

- an imagery loaded with idiosyncrasies derived from and dependent

on the tones and textures of paint on canvas, pencil on paper,

and even ink on plate or block - whose distortions of quotidian

reality mirror (or anticipate) the slippages in perception to

which we inhabitants of a complex and uncertain world are subject.

If the ideologies of the Modernist era provided at least the

projection of certainty onto a tumultuous civilization, the sociopolitical

disillusion of the last half-century has left us without such

psychological safety nets. (No wonder that so many people around

the world now resort to religious fundamentalism - or that their

fervency has now become one of the principal sources of the world's

political, and spiritual, destabilization.) The "anxious

realism" of these American artists embodies our cognitive,

even somatic, free fall. Nothing is quite what it seems - nor,

as the Zen koan goes, is it otherwise. |

Anxious Realists are at work all around the United

States, some contravening the dominant artistic discourse in

major art centers, others taking advantage of their removal from

such centers, still others responding to regional artistic environments

and traditions. Although Anxious Realism answers to a countrywide

malaise - a new age of anxiety in which the monsters under the

bed seem more potent and less placable than ever - it invariably

reflects local attitudes and circumstances. This would suggest

that the American Southeast, vaunted as a hotbed of narrative

expression and homegrown surrealism, would be especially hospitable

to Anxious Realism.

It's thus not surprising to find that the state of Arkansas alone

boasts one of America's best known and most extravagant Anxious

Realists, Donald Roller Wilson, as well as one of the subtlest,

Warren Criswell. The literary impulses of both Roller Wilson

and Criswell are quite evident, and also quite evidently different.

Roller Wilson transcends the anxiety of his realism with melodramatic

imagery, baroque humor, and an anthropomorphism so attenuated

that it at once mocks and celebrates the dogs-playing-cards tradition

of the "cute." Criswell's imagery may reach similar

levels of unlikelihood, but even his most elaborate fantasies

are rooted in human behavior, in the conventions of seeing, and

in formalized, readily recognizable modes of visual-verbal storytelling

such as theater, film, and opera. If we can think of them as

filmmakers rather than painters, Roller Wilson is an animator

(in many senses of the word), while Criswell directs live people

(although clearly willing to drop in a few special effects where

needed). |

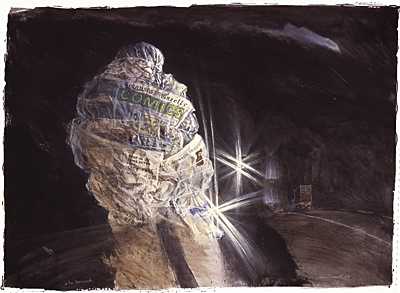

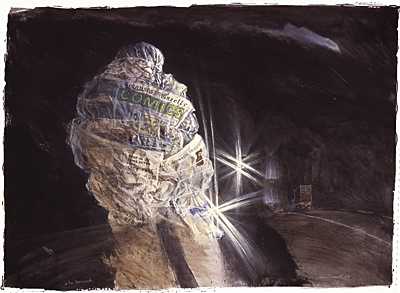

The Navigator, 1987, pastel & spray

enamel on paper, The Navigator, 1987, pastel & spray

enamel on paper,

30 x 40 inches. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation

Purchase: Tabriz Fund, 1988. 87.031 |

What connects the two Arkansans' otherwise

disparate styles so emphatically is their shared lack of irony.

They mean what they paint. Roller Wilson's apparitions, linked

in their staggering narrative arch, are clearly as heartfelt

as they are zany. And Warren Criswell's pictures, whether of

climactic moments in an operatic Gesamtkunstwerk or of strange

and poignant moments in an everyman's life, brim with the same ingenuousness - the same

commitment to this vision and to the sympathetic character of

its protagonists. These painters need to paint these things,

in these ways.

|

|

Criswell's earliest mature work is, not surprisingly,

his most prosaic. Grounded in the conventions of photo-realist

painting, if slightly less dependent on the exact translation

of camera to canvas, his work of the 1970s cleaves to the banality

of the life and lives around him. |

The Open Road,

1988, oiil & pastel on paper,

33 x 45 inches. Collection Arkansas Arts Center Foundation |

Sunday at Yogi's,

1979, watercolor, 24 x 36 inches.

Collection of Janet Criswell |

That life and those lives would remain Criswell's

principal preoccupation, but as of 1982, he could no longer adhere

to the homey mereness of their surface appearances. Increasingly

painterly in technique and interested in the effects of light

and night, Criswell began to imbue, or at least surround, his

subjects with a preternatural immanence, a glow, lyrical and

ominous by turns, that gave heightened meaning to even the most

mundane of still life subjects. In this magical chiaroscuro,

coins and keys and cups as well as people and buildings and roads

become pregnant with implications, as if props in a drama. |

Continued

1 | 2 | Next>> |

|

|

Warren Criswell

Home Page

The exhibition catalog, Warren Criswell

Shadows, in which this essay appears is Copyright 2003 by

the Arkansas Arts Center

All images and text on this Web site

Copyright © 1997 - present

by Warren Criswell

|